The before and after of a historic ruling

In the mid-1990s, European soccer experienced a turning point that forever altered its economic and competitive structure. The Bosman Law, derived from a ruling by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in 1995, radically transformed the relationship between clubs and players, marking the beginning of modern soccer as we know it today.

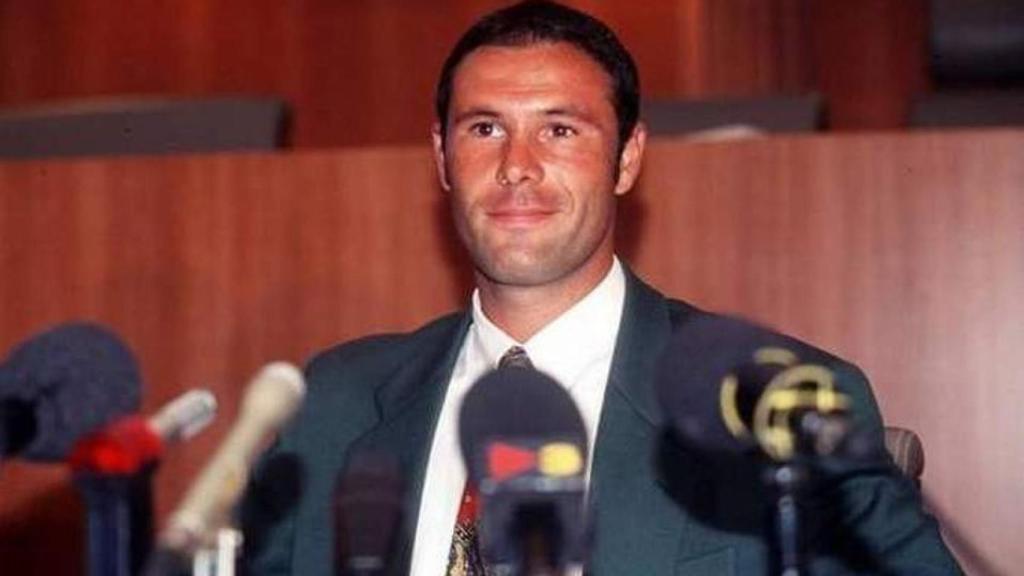

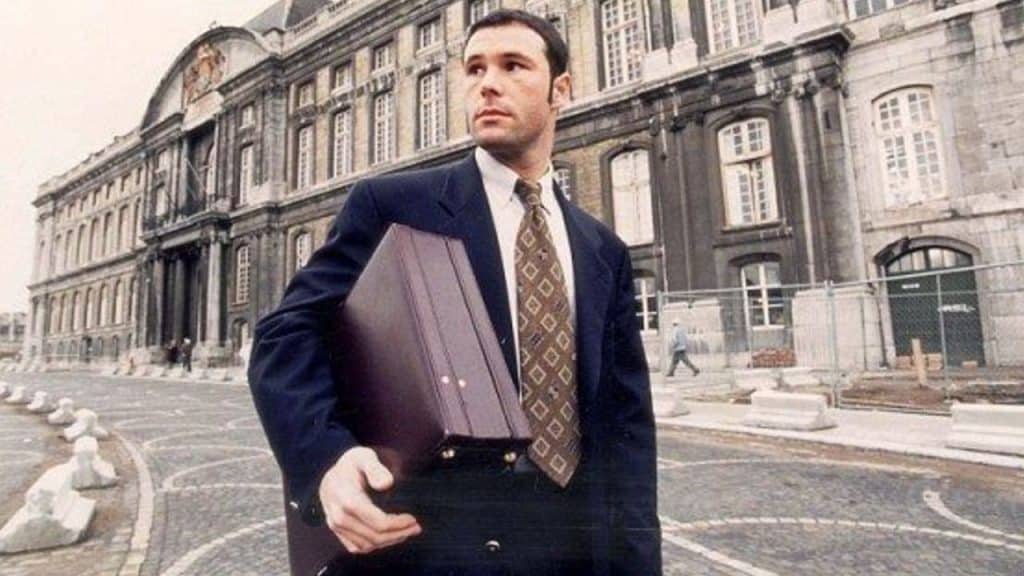

Until that time, players had no total freedom to decide their professional future, even when their contracts had expired. Clubs retained rights over them and could demand compensation or block transfers. The case of Jean-Marc Bosman, a Belgian player in conflict with his club, RFC Liège, triggered a legal battle that brought down this system and opened the door to a new era: that of the free player and the globalization of the soccer market.

A closed soccer with rigid structures

Prior to 1995, European soccer was governed by rules that favored the clubs’ absolute control over their players. Even after the expiration of a contract, the club retained the player’s federative rights, which meant that no other club could sign him without paying financial compensation.

This restriction was compounded by foreigner quotas: in the main European leagues, clubs could only field a limited number of non-national or non-locally trained players. This system, inherited from previous decades, sought to protect local talent and maintain domestic competitiveness, but in practice limited the free movement of workers within Europe.

Soccer, until then, operated under a closed, hierarchical and protectionist model, where players had little say and clubs dominated negotiations.

The Bosman case: a conflict that reached the European justice system

In 1990, Jean-Marc Bosman, a midfielder with RFC Liège, terminated his contract and wanted to join French club USL Dunkerque. However, Liège demanded compensation for his transfer, despite the fact that his employment had ended. Faced with the player’s refusal to accept a new contract at a reduced rate, the Belgian club suspended him and blocked his transfer.

Bosman decided to take his case to the Belgian courts and, subsequently, to the Court of Justice of the European Union. He claimed that the transfer rules and quotas for foreigners violated Article 48 of the Treaty of Rome, which guaranteed the free movement of workers within the European Economic Community.

The case took five years to resolve, but on December 15, 1995, the CJEU handed down a landmark ruling: the rules preventing the free mobility of EU players were contrary to European law.

The ruling: free circulation and end of quotas

The Bosman ruling established two key principles:

Free movement of EU players: any player from a European Union country could freely change clubs at the end of his contract, without the club of origin being able to demand any compensation.

Elimination of quotas for EU foreigners: clubs could no longer limit the number of European players in their squads or line-ups, as long as they were EU citizens.

These measures put soccer players on an equal footing with any other worker within the European area, consolidating the principle of labor equality and dismantling a system of control that had prevailed for decades.

The immediate consequences: a market without borders

The ruling had an immediate and profound impact. For the first time, community players gained full autonomy over their careers, and clubs were forced to redefine the way they managed contracts and transfers.

The main consequences were:

Increased labor mobility: soccer players were able to negotiate directly with other clubs without restrictions or abusive intermediaries.

End of post-contract indemnities: free transfers at the end of the contractual relationship became common practice.

Wage inflation: players began to receive higher salaries and signing bonuses, as the transfer savings went to them.

Internationalization of leagues: teams such as Arsenal, Inter Milan and Real Madrid began to build squads with players from all over Europe.

In just a few years, European soccer went from being a nationalized market to an open, competitive and globalized one.

The structural impact: from the power of the clubs to the power of the players

Beyond the immediate effect, the Bosman Law changed the balance of power within soccer. Whereas previously the clubs controlled the destiny of the players, after the ruling a new dominant player was consolidated: the professional soccer player, backed by his agents and by free competition between entities.

This transition brought with it a change in the economic structure of soccer:

Increased bargaining power of the players, who began to sign shorter contracts or contracts with specific clauses to maintain their future freedom.

Growing influence of representatives, who became key players in the industry.

Reconfiguration of the transfer market, where age, end of contract and nationality became determining factors.

The Bosman case also influenced the creation of subsequent legal figures, such as the Webster case (2006), which allowed players to terminate long-term contracts under certain conditions.

The globalization of European soccer

The opening of the EU market led to a process of accelerated globalization. The most powerful clubs took advantage of the new regulations to build multinational squads and project themselves internationally.

The English Premier League, Italian Serie A and Spanish La Liga benefited enormously from this new context, attracting players from all over Europe and the rest of the world. European soccer became an interconnected global market, driven by television rights and free labor mobility.

At the same time, the national youth academies lost prominence and many medium-sized clubs found it difficult to compete financially against the large financial conglomerates of modern soccer. The Bosman Law, in this sense, widened the gap between rich and poor clubs, but also raised the quality and spectacle of European soccer.

Criticism and collateral effects

Despite its advances in labor rights, the Bosman Act was not without its critics. Some specialists argue that the absolute liberalization of the market unleashed uncontrolled wage inflation and favored the concentration of talent in the most powerful clubs.

It is also noted that the elimination of community quotas weakened the development of local players, forcing many federations to create new regulations – such as UEFA’s “home-trained player” rules – to preserve the national identity of the leagues.

On an ethical level, soccer went from being an industry controlled by clubs and federations to a business dominated by markets, agents and investment funds, where long-term contractual stability became the exception.

Legacy and validity of the Bosman Act

Three decades after its enactment, the Bosman Act remains one of the legal and economic pillars of modern soccer. Its impact transcends the sporting: it redefined the notion of freedom of labor, professionalized management structures and consolidated soccer as a multi-billion dollar global industry.

The ruling not only changed the rules of the game, it changed the game itself. Without it, it would be unthinkable to imagine the free flow of stars between leagues, million-dollar contracts, or even the current UEFA Champions League model.

The beginning of modern soccer

The Bosman Act marked the end of traditional soccer and the birth of globalized soccer. What began as an individual dispute became a structural revolution that gave players freedom, boosted competitiveness and changed the economic basis of the world’s most popular sport.

Jean-Marc Bosman never personally enjoyed the riches generated by his cause, but his name was etched in history. His judicial struggle not only freed footballers from a restrictive system, but opened the way to a new soccer order, where mobility, competition and the market became the new rules of the game.